By Børge Solem - April 2025

Images from the Steerage – in the Age of Photography

In recent years, it has become increasingly popular for descendants of emigrants, as well as historians and writers documenting emigration history, to showcase illustrations of the ships that carried emigrants across the Atlantic and the conditions on board. Particular attention has been given to the areas where emigrants spent their voyage. Most of them traveled in the cheapest class, known as "steerage" or third class, where conditions were far from as comfortable and luxurious as those in second or first class. There has been a growing interest in images that depict the realities emigrants faced during their journey.

However, finding detailed photographs of steerage or third-class accommodations on the ships that transported emigrants from Europe to America is challenging. Most surviving images focus on the luxury cabins and upper-class accommodations from the golden age of transatlantic travel, as these were more frequently documented. First- and second-class spaces were often more ornate and were the primary focus of promotional materials aimed at wealthier passengers who could afford the higher fares.

Steerage and third-class accommodations, by contrast, were rarely featured in marketing materials, as they were not intended to attract affluent travelers. Additionally, most emigrants could not afford a personal camera, making privately taken photographs of steerage conditions exceedingly rare. The few existing images were often taken by wealthier second- or first-class passengers and typically show emigrants gathered on deck. Interior photographs are even scarcer. The dim lighting in steerage compartments made it difficult for amateur photographers to capture images, and even if they had the means, they generally had no access to these restricted areas.

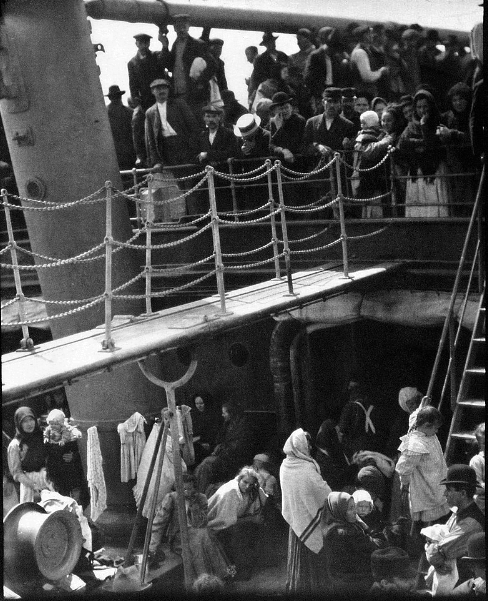

Some very few photographs of everyday life abouard taken by professional pohotograqphs does exist. The photo to the left was taken by Knud Knudsen in connection with the steamship Haakon Adelsteen's departure with emigrats from Bergen to New York on April 24, 1873. Knudsen is regarded as one of Norway’s most important landscape photographers of the 19th century. Knudsen was the first to systematically photograph the entire country, and by 1898 he had amassed a collection of around 9,000 images from across Norway.

Taken in 1873, this evocative photograph captures the crowded deck of the steamship moments before departure, as emigrants prepare to leave their homeland behind. Men, women, and children are gathered among ropes, cargo, and maritime equipment, their blurred figures reflecting the urgency and movement of the scene. The steam funnel and rigging rise behind them, anchoring the image in the age of industrial migration. The photographer, working with the limited technology of the era, faced considerable challenges: long exposure times required subjects to remain still, making motion blur inevitable amid the bustle of departure. Lighting conditions and the constraints of early camera equipment made such dynamic scenes difficult to capture, lending this image a rare and powerful sense of immediacy and human presence.

Almost all known interior photographs were taken at the request of shipping companies, either for documentation purposes or for use in promotional materials aimed at prospective emigrants. These images were carefully curated to present the ships in a favorable light, rather than to provide an accurate depiction of steerage conditions. In general, one can say that the further back in time you go, the harder it is to find photographic material of steerage or third-class accommodation on the emigrant ships.

Over the past 30 years, I have been fortunate to come across a number of rare images from various sources, which I have secured for the collection whenever possible. In the following, I will present some of these scarce glimpses into the past.

The Circular Photographs of Early Kodak Cameras

Before the introduction of Kodak No. 1 in 1888, photography was a complex and expensive process, accessible only to professionals and dedicated amateurs. Taking photographs, especially while traveling, required bulky cameras, fragile glass plates, and portable darkrooms. Most travelers relied on professional photographers or pre-made souvenir images, as carrying photographic equipment was impractical.

Kodak changed this with the first consumer-friendly camera, featuring preloaded roll film and producing distinctive circular photographs (approximately 6 cm in diameter). The circular format helped eliminate distortions from early lenses and provided a unique aesthetic.

With Kodak’s slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest," photography became effortless. Users simply mailed the entire camera to Kodak for film development, printing, and reloading. This innovation democratized photography, allowing ordinary people to document their travels and daily lives for the first time.

Kodak No. 1 transformed photography from a technical art into a popular hobby, paving the way for modern personal and travel photography.

From Circular to Rectangular - Capturing the moment

After the success of Kodak No. 1 (1888), Kodak continued refining its cameras. Early models, like Kodak No. 2 (1889), still produced circular photos, but by the 1890s, folding cameras with rectangular formats started gaining popularity. The real shift came with the Kodak Brownie (1900)—a simple, affordable box camera that used 120 roll film, making rectangular images the new standard. By 1905–1910, rectangular images had fully replaced circular ones in amateur photography. Kodak remained dominant, but faced competition from brands like Ansco, Zeiss Ikon, and Leica. The introduction of 35mm film (1925) by Leica marked the next major transformation, paving the way for modern photography.

On May 14, 1907, Alfred Stieglitz, an American photographer and promoter of modern art—sailed to Europe aboard the fashionable Kaiser Wilhelm II. At the time, he was using a hand-held 4×5 Auto-Graflex camera with glass plate negatives. During the voyage, Stieglitz captured what is now recognized not only as his signature image, but also as one of the most important photographs of the 20th century. Many consider it to be the first truly modernist photograph. The photograph is one of the most well-known from "The Steerage," but Stieglitz was not the first to photograph life in the steerage. Nor was he the only one.

To the left, two other amateur photos captured circa 1904 aboard the Norddeutscher Lloyd liner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. This evocative amateur photograph presents a vivid tableau of steerage passengers assembled on the ship's deck during an Atlantic crossing. The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, launched in 1897, was a landmark vessel of the German maritime fleet — renowned as the first superliner and a proud bearer of the Blue Riband for the fastest transatlantic crossing. In the image, the decks are visibly crowded with men, women, and children of varied origins bound for the United States. The faces of the passengers — some solemn, others curious — offer a silent narrative of hope, uncertainty, and endurance. The close quarters and dense arrangement of bodies on the deck reflect the realities of steerage class travel: confined spaces, communal conditions, and limited comfort. Yet, within the visible hardship lies a quiet dignity, as these individuals stood on the precipice of transformation — leaving behind ancestral homelands to seek new identities and opportunities across the ocean.

The photograph, though taken by an amateur, holds considerable historical significance. It documents not only the physical structure and social environment aboard an emblematic early 20th-century ocean liner but also encapsulates the spirit of transatlantic migration—one of the most defining movements of the modern era.

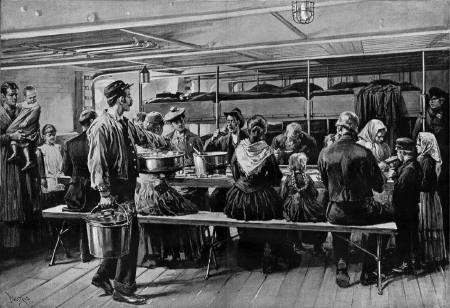

The interior photograph to the left was taken by Norwegian photographer A. B. Wilse, some 16 years after he had himself experienced the hardships of traveling as a steerage passenger. It offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the lives of steerage passengers aboard a transatlantic vessel in 1904. The image was taken within the confines of the steerage compartment — a section of the ship typically reserved for economically disadvantaged immigrants seeking new opportunities in the New World.

The scene from the the sleeping quarters reveals a crowded, low-ceilinged interior lined with iron support columns and utilitarian metal-framed bunk beds, each marked by numbered plaques — indicating the strictly regulated accommodations. A diverse group of individuals, comprised of women, children, and men, gaze toward the camera with expressions ranging from curiosity to fatigue. The clothing is modest and practical, consistent with the working-class origins of many immigrants of the time.

The second photograph depicts a lively and crowded dining scene in the third-class, or steerage, dining saloon of steamship Hellig Olav. Men, women, and children, are gathered around long communal tables, partaking in a simple meal. The table is set with plain crockery, and the food appears basic, reflecting the practical yet austere conditions provided for steerage passengers. We can see the passengers have been served soup, accompanied by a platter of traditional Danish ankerstokk bread, or dark rye bread.

The presence of multiple young children evokes the family-centric nature of immigration during this era, when entire households would endure the arduous journey in hopes of a better future. The sparse and confined setting illustrates the hardships faced by steerage passengers — limited privacy, basic amenities, and the long, often uncomfortable voyage across the Atlantic.

This image serves not only as a visual document of migration history but also as a testament to human resilience and aspiration, encapsulating the lived experiences of millions who embarked on similar voyages during the great waves of immigration.A Photographic Glimpse Below Deck.

After the turn of the 20th century, it became increasingly common for shipping companies to promote their vessels directly to prospective emigrants. Competition among the major transatlantic lines was fierce, and the potential for profit from the mass transport of people was significant. As a result, shipping lines began designing vessels more thoughtfully, with third-class accommodations gradually being improved to better meet the needs of their primary passengers: emigrants.

To market these developments, companies produced brochures and promotional materials featuring photographs of their ships. Professional photographers were now commissioned not only to capture exteriors and first-class saloons, but also the interiors of steerage and third-class quarters. These images marked a shift in how emigrants were perceived — as valued customers rather than anonymous masses below deck.

Some of these early promotional photographs have survived, while others exist only in the form of low-resolution reproductions in printed handbooks or brochures. Even though most of these photos were staged and taken without passengers present, they still provide valuable insight into how third-class accommodations were arranged and presented during the golden age of transatlantic migration.

These rare interior photographs taken aboard one of the Cunard Line’s great steamships, offer more than a visual record of third-class accommodation. They provide a powerful lens through which to consider the lived experience of transatlantic emigrants, whose journeys unfolded far from the opulent staterooms usually associated with ocean liners.

At first glance, the images show a functional interior, composed of metal-framed bunks, stacked in rigid tiers, and long wooden tables set with plain white tablecloths. The tight spacing of the beds, the shared tables nestled between them, and the lack of partitions or personal storage speak to the overcrowded and communal nature of steerage life. The passengers are absent — but in their absence, the images seem to echo their presence. One can imagine the noise, the constant movement, the smell, the soft murmur of multiple languages in close quarters.

An emigrant who traveled on the Lucania in June 1896 described the conditions as follows:

"Steerage No. 1 is virtually in the eyes of the vessel, and runs clear across from one side to the other, without a partition. It is lighted entirely by port-holes, under which, fixed to the stringers, are narrow tables with benches before them. The remaining space is filled with iron bunks, row after row, tier upon tier, all running fore and aft in double banks. A thin iron rod is all that separates one sleeper from another. In each bunk are placed "a donkey's breakfast" (a straw mattress), a blanket of the horse variety, a battered tin plate and pannikin, a knife, a fork, and a spoon. This completes the emigrant's "kit," which in former days had to be found by himself.

This steerage, with a capacity of 118, was kept solely for English-speaking males. Directly below it was steerage No. 2, of similar size, intended for foreign males. A little farther aft was steerage No. 3, with accommodations for 172 sleepers. Abaft on the port side, two flights take one down to the "married quarters." The single females are stowed in "pockets" on both sides of the ship. These, in distinction from the men's quarters, are divided into rooms holding from four to sixteen persons, and have a common room for meals.

To the credit of the ship, it must be said that everything was clean. Sweet it was not. Spotless, sanded decks, scrubbed paintwork, and iron bunks could not hide the sour, shippy, reminiscent odor that hung about the steerages, one and all. In the half-light of the great tween-decks my companions were busy establishing themselves. As many of them evidently carried all they possessed in their hands, the bunks were soon piled with a strange assortment.

Carpet-bags, brown-paper parcels, cooked victuals, underclothing, fruit, bird-cages, and sundry loud-smelling, suspicious-looking bottles, were frequently seen. Strange to say, nearly every one seemed to be provided with a specific for seasickness. One man had apples, another a patent medicine, a third carried a pocketful of lime-drops, and yet another had pinned his faith upon raw onions.

At four bells I went below. With the exception of one group carousing, I found all turned in. Few of them were asleep, however. A good half sat propped up in their bunks, early victims to seasickness. As our steerage was so far forward, the motion of the vessel was violent, and this, with the stifling atmosphere of the place, the stench, and the unearthly noises of the sick, nigh sent me back on deck again. Rallying, however, I picked my way along a slippery aisle, and reached my berth. It was a top one, thank Heaven, and the middle of a row of five. The other four bunks being tenanted, I had no means of entering my own but through the stanchions at the foot; and this I did with many a suspicious look at the prostrate forms on each side. Take away the thin rods, which, after all, were almost as imaginary as the equator, and our row was simply a bed for five, with myself in the middle. A few of the men had taken their coats off and placed them under their heads for pillows; but most lay as they had stood, with boots, coats, and, in many cases, their caps on. After building a barricade of bags and blankets on each side, I lay down in the middle, and got a few hours’ sleep. One night of it, however, was sufficient. For the remainder of the passage, I slept on deck."

I hope you found this brief glimpse into the visual material—and the stories it reveals—both interesting and informative. If you would like to explore more images from the "steerage," you can discover many additional photographs and other images in our image gallery here: Image Gallery. Type "steerage" in the search box, and the results will appear. If you would like to send me a comment please do so at: borge@norwayheritage.com